Here is the final chapter to Module 6 and the last posting of my Diploma

Stitch:

functional or decorative?

Stitch

in textile art – is it functional to the physical integrity of the artwork, or

purely decorative and thereby the definer of artistic quality?

It is

not a question I had generally considered when viewing textile art; after all

it is not something that comes to mind looking at gallery paintings or

ceramics. The paint strokes clearly do

not hold the painting together or the glazes the clay, and yet they impart a

texture, a movement and an aesthetic to the work that is present in many

beautiful weavings borne out of functional stitches.

The

weaving and coiling of Indigenous Australian artists researched during my last

diploma module of work are clearly functional in their creation of vessels from

grasses, but also highly decorative in stitch technique and adornment. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Fibre sculpture detail by APY*

artists

This

fibre art enables the artists to express their culture and interest in their

local habitat in the form of highly tactile sculptures. They have a drive to create in this way, and

a desire to continue the creation by passing on traditional skills to the next

generation. This passion led me to think

of three British textile artists whose works exude their enthusiasm for stitch

and inspire me to express myself in textiles: Jan Beaney, Sue Hotchkis and

Alice Kettle.

Jan

Beaney is a renowned embroiderer, teacher, author and exhibitor in the UK and

worldwide. She can employ mixed media,

paint, beading and other contemporary materials into her work as the subject

demands, but always with hand and machine embroidery as the principal

players. Like the Indigenous artists, she

finds inspiration in the landscape around her and beauty in the mundane and

everyday details. The focus of

indigenous art is often the locale and activities surrounding the artists. Their fibre sculptures may be simplified to

the point of schematic but the source of their design lies in local wildlife

and vegetation. Jan may not be using

tangible vegetation in her work but her design sources lie similarly close at

hand.

Over

recent years she has used a water-soluble material on which to stitch, connecting

fragments such as fabric scraps and wool roving through hand and machine stitch. Once the fabric is washed away a complete new

“cloth” remains on which further stitching can be done. This is clearly a situation where stitch is

both functional to the created cloth and decorative. The combination of hand and free machine

stitch gives a wonderful texture and depth to the work. Hand embroidery in various weights of thread

and wool, and in different type and size gives tremendous detail in layers of stitching. Free machine embroidery then integrates and

embeds the stitches, blending colour and its movement within the piece.

Whether

her work is densely layered (Figure 2) or translucent to the point of extreme fragility

(Figure 3), the compositional thought involved and skilled execution is always

there and entices one to look ever closer.

|

| Figure 2: New Life (2008) Jan Beaney, private collection |

Figure 3: Skala Eressos – Early Evening (2009) Jan

Beaney from scan of postcard

I love

the way Jan blends and layers large bold hand stitches in thick wools with

fragments of scrim material and wool roving (Figures 4 and 5). It appears too great a contrast up close but

simply gives enough texture interest when one steps back. I have learned from this to continually stop

and view ones work from a distance.

Fresh eyes from a different perspective are the key to self-critiquing.

.

Figure 4: New Life detail

Figure 5: New Life detail

It is the

wish to entice the audience to look closer that I also endeavour to reach, and

therefore it is not surprising that her use of hand and machine embroidery has

been influential in my work. In Lichen, I sought to bring detail and

texture to dimensional nunofelting with significant hand embroidery in

different weights of wool and pearlised cotton (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Lichen detail (2016) Helen MacRitchie

In

researching Lichen I came across a

recent textile of the same name by Sue Hotchkis, a UK artist now living in

Guernsey. I had seen glimpses of her

work over the last few years, glimpses of amazing layered texture, freely

embroidered but only this year had the opportunity to discuss her work with her,

first hand, while she was solo exhibiting in Fragments in Australia.

She

too is drawn visually to the details of living, drawn to photograph the torn

posters, the rust and wear, the detritus of modern life. She sees beauty in the

detail that is often missed on first glance.

Her inspiration and subject

matter may be far from exciting in name but once they abstractly transform into

such jewelled fragments of stitched detail, they come alive.

She

employs digital printing, screen printing, paper lamination, trapunto, free

machine embroidery to name but a few contemporary techniques, building and disintegrating

layers and fragments (as her exhibition was so aptly named) into detailed sculptural

hangings (Figures 7 and 8)

|

| Figure 7: Door detail Sue Hotchkis |

|

| Figure 8: Fifty-two detail Sue Hotchkis |

Her stitching is functional, combining layers and fragments into a cohesive hanging, but of course it is also highly decorative. Without her extensive embroidery much surface detail and sculptural manipulation would be lost and the fragment cohesion diminished.

She

describes her stitching process as meditative. She becomes almost lost in the rhythm

of machine stitching, merging fragments and creating texture, reminding me of

the repetitive weaving involved in Indigenous fibre art. Such dedication to the process is apparent;

never invisible to the close examiner. I

also see the employment of new technologies such as digital printing which are

at hand to the contemporary textile artist, an extension to the materials at

hand to the Indigenous artist. The

techniques may have changed but the opportunistic approach to available

resources has not. I love her striking

use of colour, particularly her combinations of complementary colours as in Verdigris (Figure 9), and the tonal

variations within pieces, such as Embrace

(Figures 10 and 11), giving them

real depth.

|

| Figure 9: Verdigris detail Sue Hotchkis |

|

| Figure 10: Embrace detail Sue Hotchkis |

|

| Figure 11: Embrace Sue Hotchkis |

|

| Figure 12: Loedhas Helen MacRitchie |

Another

UK textile artist who has found her own medium in which to express her art

practice is Alice Kettle. Alice is

currently Professor in Textile Arts at Manchester Metropolitan University

having studied fine art as an undergraduate working in abstract expressionism,

and then pursuing textile art as a postgraduate. She has established a unique position in the

fibre arts field creating heavily stitched wall hangings, using extensive free

machine embroidery and layering threads of different weights and thicknesses on

a cloth background. She often chooses

as inspiring subject matter, historical characters and tales, mythological

stories, and figurative representations.

In her pictorial pieces, there is rarely a literal connection to her

theme, more often a symbolic one. This

is reminiscent of the markings found in Indigenous art e.g. circles representing

homesteads or gatherings, meandering lines as rivers, movement or animals. Their

culturally important people and story creatures are represented symbolically in

their fibre sculptures. In Alice

Kyteler (Figure 13) the central figure may indeed be the old woman of that

name but Alice gives her a sense of regal majesty inferring her power and

strength of character through the adornment of her skirt in textile ephemera and

her compositional placing in lightness with metallic threads.

Figure 13: Alice

Kyteler Alice Kettle, photo taken from www.alicekettle.com

I

briefly studied Alice in a previous module of diploma work, but since then I

have examined some of her commissioned installations more closely and had the

opportunity to hear her speak in conference about her work. I did not fully appreciate before her

painterly approach to her work. She expresses her love of the physical nature

of paint, the gestural nature of mark making, and her desire to translate her

fingerprint in painting into textiles.

She layers threads in her stitching to convey the fluidity of painting

strokes, playing with threads of different colour, thickness and shine. Different qualities in light reflection are

achieved by layering glossy and matt threads, which let the viewer “go into”

the surface of the threads. She tries to

“float” a matt thread over areas of metallic to give depth and alter the light

resonance between threads. I am

fortunate enough to own a textile Daniel

and the Lioness (Figure 14), by

Alice Kettle, and can appreciate this effect at first hand – aspects of the

surface appear differently coloured and reflected as you move past in different

light.

Figure 14: Daniel and the Lioness Alice Kettle, private collection

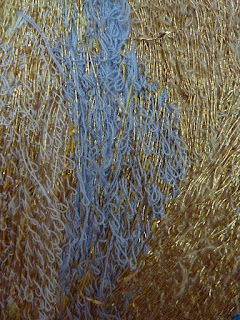

Threads

are layered in different directions (Figure 15), some stitches tiny others

huge, whipstitching colours from beneath appear (Figure 16), and loops of

thread jump off the surface (Figures 17 and 18).

Figure 15: Daniel and the Lioness detail 1 Alice

Kettle

Figure 16: Daniel and the Lioness detail 2 Alice

Kettle

|

| Figure 17: Daniel and the Lioness detail 3 Alice Kettle |

|

| Figure 18: Daniel and the Lioness detail 4 Alice Kettle |

The

fascinating detail is there on close examination but the joy is apparent when

you step back. It then becomes less

about the individual stitches and more about the movement and light conveyed

across the whole textile. It could be

said that each stitch is decorative but I feel they are not to be admired in

isolation – rather they exist ‘en masse’, creating a fluidity of colour and gesture

true to Alice Kettle. In that sense they

are indeed functional, and successful in achieving that goal.

Mark

making through stitch takes many forms: functional and decorative. My study of

these three artists for whom mark making has great affinity, has shown me that be it in the creation of soft textural

colour blends, the effect of abstract paint strokes, or organic sculptural

detail, stitched textiles are a feast for the eyes and an inspiration to us

all.

Helen MacRitchie 2016

All

photographs are my own except where noted.

*APY:

Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunyjatjara

References:

Jan

Beaney and Jean Littlejohn (2010) Stitchscapes,

published by Double-Trouble, UK

Jan

Beaney and Jean Littlejohn (1998) Stitch

Magic: Ideas and Interpretation, published by Batsford, UK

BeCreative with Workbox magazine (2015), May/June

Embellish

magazine (2016) Vol

25 March

Embroidery magazine (2016), Jan/Feb

issue, Craft, Credo & Collaboraton,

pp28-33

Carol

Shinn (2009), Freestyle Machine

Embroidery, published by Interweave Press USA

Diana

Springall (2005) Inspired to Stitch,

published by A&C Black Publishers, UK

www.alicekettle.co.uk/exhibitions/narrative-line/

www.suehotchkis.com

www.textileartist.org/alice-kettle-reinvent-rework-reconstruct/

www.textileartist.org/jan-beaney-and-jean-littlejohn-interview

www.textileartist.org/susan-hotchkis-conception-creation/

www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/i/interview-alice-kettle-embroiderer/